A couple of months ago, I attended my first-ever conference for mystery writers. And while it was a wonderful experience in many ways, something has been nagging at me ever since. Today, while sipping a cappuccino at Starbucks alongside private investigator Sid Rubin, I figured it out: many of the male crime novelists I met boasted about the female protagonists they created as “She kicks ass and takes names,” or “She takes names and kicks ass,” or just plain “She’s a hard-ass.”

How irritating. It made me wonder whether those writers believe that in order for a female detective to be worth writing or reading about, she has to be as tough as nails.

I maintain that a person doesn’t need to be tough to be successful at their job. As someone who earned the nickname “The Velvet Hammer” during my days in hi tech, I can attest to the fact that femininity and effectiveness are not diametrically opposed. And it’s reflected in the protagonist I created. As a friend said recently, “Maxime doesn’t seem overly concerned about his masculinity,” which was a lovely way to say that my protagonist is not a hard-ass. He doesn’t need to be in order to be a successful sleuth.

I ran my thinking past Sid, who was kind enough to let me interview him for this blog. He even paid for my cappuccino. Sid is ex-military and ex-FBI. He “packs heat” on occasion and could very well have been concealing a firearm in his leather jacket right there in Starbucks. He’s also a gentleman. If he is a hard-ass—and I can easily imagine how he would be out in the field—he didn’t so much as hint at it. He didn’t trot out a litany of tough cases he cracked or try to impress me with ham-handed references to his 25-year career as a Special Agent, his success as a private investigator, or his intimate understanding of law enforcement. He’s surprisingly soft-spoken, and when not being grilled (gently) by me, he talked openly about how much he loves his wife and looks forward to hosting pajama parties for his grandkids. He gave me no indication that a woman has to be man-like to be a successful P.I. herself. In fact, more than once he stressed that you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.

So after a nearly three-hour conversation, I asked Sid to summarize the information he shared with me as pearls of wisdom. He suggested that some of what I was calling “pearls” might in fact be grains of sand. (Somehow, I don’t think a hard-ass would do that.) But in my opinion, they are indeed pearls because they offer a lot of value to aspiring private investigators, and some of them are life lessons too.

So without further ado, here are Sid’s pearls of wisdom…

1. Get a background in law enforcement.

According to Sid, the more experience you gain in local, county, state, or federal law enforcement, the more it will benefit your career as a P.I. There are some things—like interviewing techniques, usage of proprietary databases, and development of information sources—that can be taught in a classroom but are significantly enhanced by field work experience. Sid should know because after leaving the FBI, he taught Criminal Justice at community colleges and trained police officers.

2. Beware of a badge-heavy attitude.

If someone accuses you of being “badge-heavy,” it means you’ve adopted a persona of being powerful because you have a badge or license. It’s not a compliment; it’s a warning against assuming you have to assert power because you’re licensed to investigate.

And that includes waving a gun around. Case in point: Sid has a weapon permit but he carries his firearm only when he’s in a dangerous place where he has a valid concern about his personal safety.

3. There’s an easy way and a hard way.

I’ll bet Sid has repeated that phrase countless times when he’s pursuing someone or just conducting an interview. For instance, the easy way might be sharing information with him; the hard way would be sharing it with the prosecuting attorney.

He shared a hilarious story in which he had to search a house for a fugitive. Though he was told by the other Special Agents that the house was “cleared,” he was surprised to come face-to-face with a human posterior sticking out from a shelf above the washer and dryer in the laundry room. He directed the suspect to come down from the shelf, but to no avail. Sid informed the fugitive that he could come down the easy way or the hard way—the decision was his. Still no response from the protuberant posterior. So without warning, Sid climbed on a chair, grabbed the man by his belt and the waist of his pants, jerked him off the shelf, and let him bounce onto the laundry machines where he was handcuffed.

Easy way or hard way. You could say that the man found out the hard way just what the hard way was.

4. Seek cooperation, not confrontation.

When interviewing someone, the trick is to get them to want to give you the information instead of trying to force it out of them. Or, to refer back to an earlier Sid-ism, “You can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.”

People are often willing to cooperate for a variety of reasons: they want to be involved, it’s the right thing to do, they have something to gain, etc. Part of the trick is to figure out which one applies to the person you’re interviewing so that you can appeal to their motivation.

5. Before conducting an interview, define your goals and desired outcome.

What are you hoping to learn from an interview? Why interview one person instead of another? It saves time and effort if you’re purposeful in your approach to interviewing people. It also helps—a lot—if you’ve been trained in interviewing techniques (which Sid learned at the FBI, which trains and re-trains its agents).

Knowing what you’re after can also help you engage in the right kind of subterfuge when necessary. “An investigator will often throw things on the table to mislead a subject and get a verbal, facial, or physical reaction,” he said. He gives himself an “above average” rating at knowing when someone is lying but I’d venture that he’s way above average because he knows what he’s looking for and how to interpret someone’s reactions.

6. Establish convincing pretexts.

“A lot of P.I. work is assisted by developing pretexts,” said Sid. Before he goes into the field on a specific case, he establishes pretexts that he uses when asking people for information. For example, when looking for a stolen boat, he posed as a salesman of GPS technology to interview people at various marinas. It was a lot gentler and more effective than flashing a license and saying, “I’m a P.I. looking for information about a stolen boat.” He got the information he wanted, and successfully located the boat.

“You should have the ability to be a chameleon. If people don’t buy into your pretext, walk away and asks someone else,” he advised. “Don’t confront, don’t argue. Accept what you have and work around it.”

7. Consider alerting local authorities before you start surveillance.

Sid often calls the local police before he conducts a surveillance to give them a heads-up rather than risk neighbors calling the police to report a suspicious man spying on or stalking someone. “Some P.I.s operate in their own vacuum world,” said Sid. So don’t be one of them.

8. Develop your network.

Sid participates in a local network of retired law enforcement personnel who do P.I. work, as well as a worldwide network of about 775 retired FBI agents. Most of his work comes from law firms, large corporations when a matter is too sensitive for their own security teams, and referrals.

But what if you’re just starting out without law enforcement contacts or enough word-of-mouth referrals to get work? Sid recommends joining the Pacific Northwest Association of Investigators (P.N.A.I.) and WALI (Washington Association of Legal Investigators). “They’re great networking tools for someone setting out on a P.I. career to meet other investigators. And they’ll also help you find out what you can reasonably charge,” he said.

It also helps to develop contacts in the security industry (security departments in corporations, security firms that companies outsource work to, firms that offer private security, etc.), which can help you establish a client base.

9. The way you spend your time depends on the type of case you’re handling.

Not all private investigators drive fancy sports cars, wear disguises, and spend their days chasing down suspects and dodging bullets. Depending on the case, you might spend more time in front of a computer than in the field.

On a typical day, Sid reads his email, decides which of about 12-15 active cases to work on, prepares a schedule of which leads to follow, plans which locations to go to, and does online research in proprietary databases (TLO, IRB, and LexisNexis) available to lawyers and private investigators. “Proprietary databases are constantly being updated for accuracy so it pays to use them,” said Sid. “Public ones can contain misinformation that wastes a lot of time.”

10. The documented results prove the worth of the investigation.

The deliverable by a P.I. to their client is always a report of the results, which respond to the goals established by the client. Sid won’t invoice a client until he has a written report (or an oral report if that’s what the client has asked for instead) to accompany the invoice.

BONUS: Don’t be misled by the private investigators you see on TV.

This isn’t actually one of Sid’s pearls, but it came across loud and clear during our conversation. He listed the qualities of a successful P.I. as:

- The ability to be a chameleon (see above)

- The ability to fight boredom (especially when conducting a surveillance)

- Honesty

- Ethics

- Knowledge of the law (i.e., what you can and cannot do legally)

- Knowledge of people

- “Skillcraft” (how to perform various aspects of the job)

What you often see on TV are criminals who are clueless to the fact that they’re being watched (“People involved in criminal activity look for clues that they’re under surveillance,” said Sid), and “bumper locking” by investigators who follow a target vehicle by starting their engines at the same moment as the suspect and follow from a ridiculously close distance. Which just speaks to skillcraft—learn the skills you need because, as Sid notes, “It’s not like on TV.”

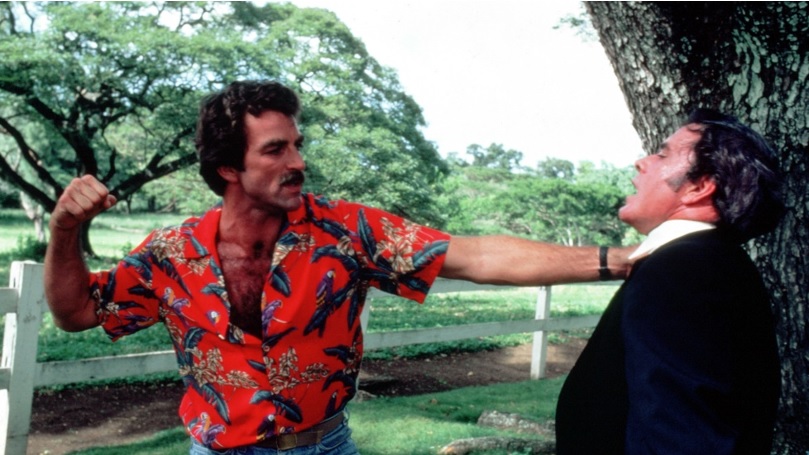

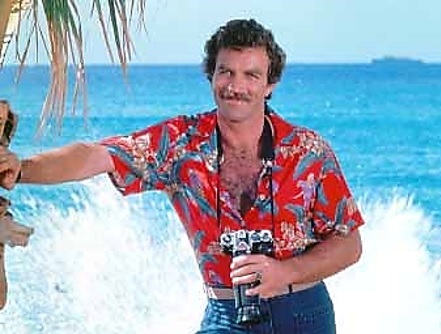

Thanks this week go to the incredibly kind and generous Sid Rubin, who made this blog post possible. I’d include a photo of him but when he wouldn’t let me use my “spy dictaphone” to record our conversation, I didn’t dare ask if I could blow his cover by taking his photo. So I’ll just leave you with this image and let you imagine what he looks like!